Re-post from UB Sustainability – News

By LAUREN NEWKIRK MAYNARD; Published February 10, 2017

The biggest problem of the 21st century, according to civil rights expert john a. powell, is the problem of “othering,” or focusing on our differences as individual deficits instead of collective strengths.

Othering comes in many forms, powell told a UB audience, but by far the most destructive in American society is systemic racism.

On Wednesday night, powell gave a highly anticipated lecture — part of his weeklong residency at the School of Architecture and Planning as the 2016-17 Clarkson Chair in Urban and Regional Planning — that packed the fourth floor of Hayes Hall. With a gentle voice and sparkling humor, he discussed the problem of systemic racism through slides full of harrowing statistics, showing how human nature works against us, and how each society has its own way of “othering” and discriminating against people it doesn’t understand.

john a. powell spoke at UB as part of his weeklong residency as the 2016-17 Clarkson Chair in Urban and Regional Planning. Photos: Douglas Levere

Research shows that our brains are naturally wired to connect to others, but also to instantly — and unconsciously — separate and categorize other people. powell explained how implicit vs. explicit bias works, or how our unconscious minds are far faster and more powerful than our slower, more deliberative consciousness.

The outcomes of our unconscious biases are alarming but instructive, powell said. Americans across all demographic lines say they don’t consider themselves racist, or sexist, or xenophobic. Yet in study after study, our subconscious minds say otherwise, he said, pointing to, for example, systemic, deeply ingrained racism that is driving social norms, from the content on our television shows, to who the police choose to arrest and who our political leaders determine are legal, law-abiding citizens.

powell then turned to the biases with which we design our built environments, including our homes, schools, churches, doctor’s offices, supermarkets, bus stations and other public and private spaces. He said the feelings these spaces create go hand-in-hand with how we perceive ourselves and others, including those of other races, ethnicities and nationalities. And our country, powell said, has done a lousy job of creating physical and social structures that bring us together to promote good health and well-being for all citizens.

He gave two examples: You walk out the door and get on a bike to get some exercise, and see trees and smell fresh air. Or you venture outside and encounter three lanes of traffic whizzing by and garbage on the street. Your fear for your safety prevents you from walking around the block. The world we’d all prefer is obvious, he said, but still out of reach for a majority of Americans.

powell, who does not capitalize his name, directs the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society at the University of California, Berkeley, and has spent his career in law and African-American studies writing and speaking on a complex array of connected issues, including structural barriers to opportunity; racial justice and regionalism; concentrated poverty and urban sprawl; fair housing; affirmative action; and spirituality and social justice, among others. He also has served as a consultant to other countries who, like the U.S., are grappling with sudden changes in society and technology.

“Rapid change has created a great deal of churn,” he told the UB audience, noting how the demographic shift from white majority to non-white majority is fully underway. “We’re reconstituting who we are.”

john a. powell (right) talks with Will and Nan Clarkson, who support the Clarkson Chair program that brings distinguished scholars and professionals to UB for lectures and seminars.

As the face of America changes, he said, this creates understandable anxiety for all races. That anxiety, combined with uneven distribution of resources like education, quality housing, food and health care, results in adverse effects on vulnerable populations, including refugees, minorities, women, children, the elderly and the disabled. Inequalities in what powell calls “opportunity structures” — illustrated by census reports and death records — show how our implicit (unconscious) biases against the “other” can also damage our living environments and the social fabric, no matter what our income and race.

The solutions, powell noted, are as complex as the problems, but they’re worth tackling. The good news, he said, is that we can literally build our way to racial and social equity. We can better adapt to rapid changes and promote more just societies by bridging differences with empathy and compassionate leadership. “We need to talk and listen to each other,” he said.

Then there’s what powell calls “targeted universalism,” which uses strategies tailored for specific groups to reach universal goals. This is an intentional inversion of traditional strategies, like universal health care, which, he said, promote a silver-bullet approach to addressing the needs of an increasingly diverse population.

“We must start asking what our final goals are. What are the intended outcomes? Then we can put systems in place that can do different things for different people with a common goal in mind,” powell said. In other words, targeted universalism doesn’t force people to change, but builds a world that supports humanity’s differences, he said. At institutions like UB, or our central government, diversity can point to collective strength, he added, helping de-escalate the country’s current obsession with shaming and exploiting “the other.”

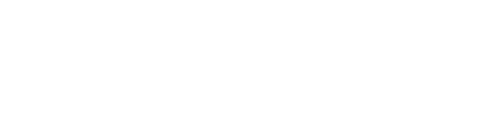

powell’s urban planning residency leaves the School of Architecture and Planning, and the university, with a new set of tools for creating positive change. The Haas Institute has established a websitepromoting the philosophy and tactics of targeted universalism. The organizing committee for his UB visit also has curated a list of more than 100 books, journal articles and multimedia resources available in the UB Libraries that explore topics of race, space, place and opportunity.

- A diverse crowd of students, faculty and members of the community attended the powell lecture.

- A large crowd packed 403 Hayes Hall for john a. powell’s lecture.

- john a. powell used numerous slides to discuss the problem of systemic racism, showing how human nature works against us, and how each society has its own way of discriminating against people it doesn’t understand.

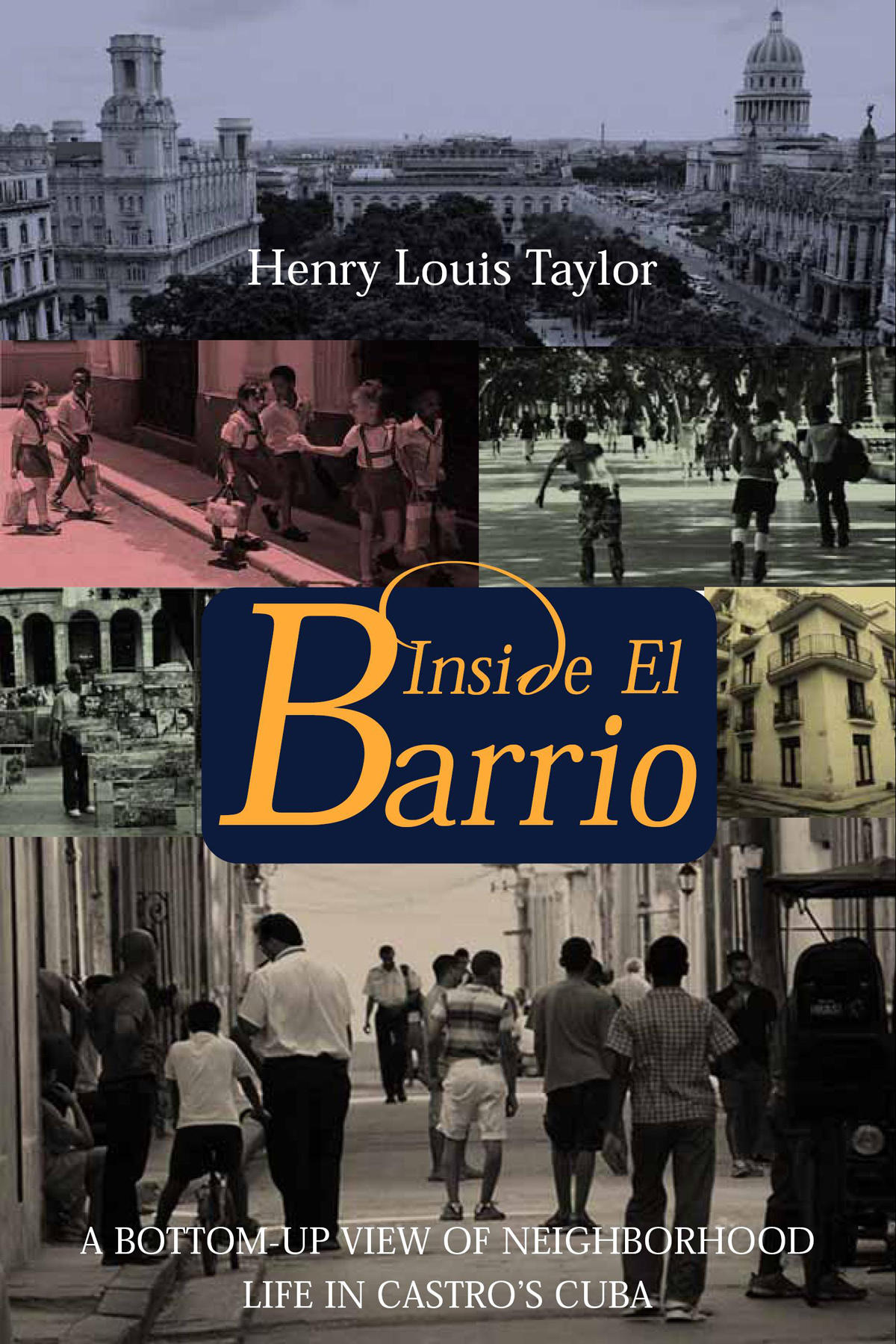

- In addition to his public lecture, which attracted a standing-room-only crowd, john a. powell took part in a community workshop and discussions with UB faculty and students, as well as policymakers and community leaders.

- john a. powell left his audience with much to think about.