From the ground up: Addressing Buffalo’s health disparities

Watch the YouTube video, here.

A formal connection between the Center for Urban Studies and the Community Health Equity Research Institute at UB is sharpening the focus on Buffalo’s built environment and its impact on the city’s social determinants of health.

To effect transformational change in Buffalo, UB’s Center for Urban Studies is joining the Community Health Equity Research Institute

Read the full article from University at Buffalo, here.

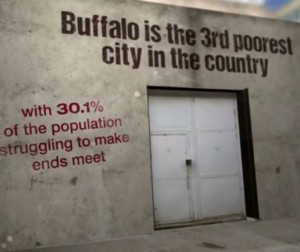

BUFFALO, N.Y. – To more powerfully address and reverse Buffalo’s entrenched health disparities, a University at Buffalo center dedicated to regenerating underdeveloped neighborhoods is joining the Community Health Equity Research Institute at UB.

“The Harder We Run” Panel Discussion

In case you missed the panel discussion for the Center’s most recent report, “The Harder We Run”, here is a zoom recording of the panel discussion: https://us02web.zoom.us/rec/share/0ZTy_hrHh_hqxZVMIgkWB4uNQ_l8ui_1B_l8cLEebdag-hszVI4a_4gvWQH8l-w0.HAXa-XGMiYa3CkDX

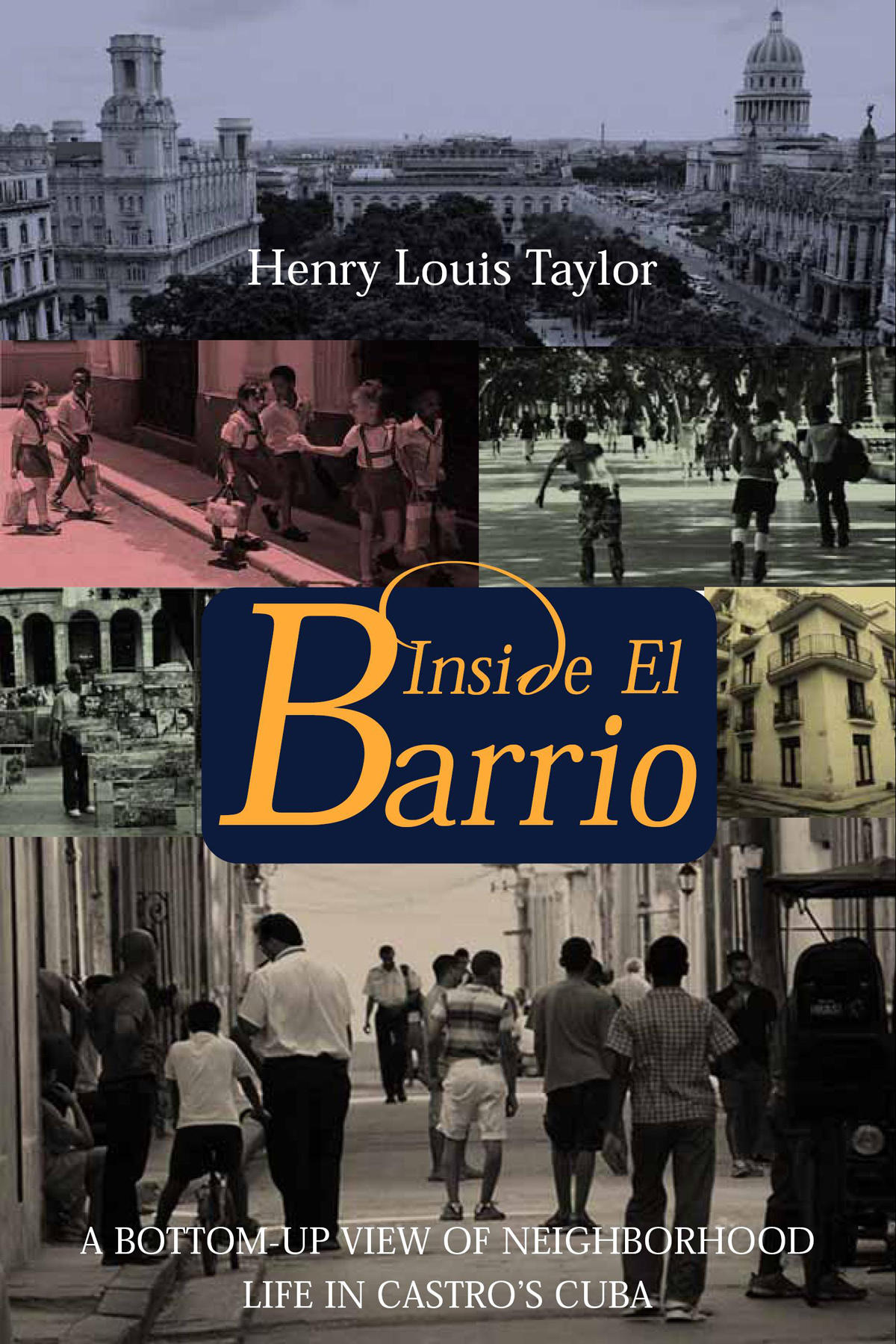

Mark Scheer interviews researcher Henry-Louis Taylor on new report

Reporter Mark Scheer interviews Henry-Louis Taylor, director of the Center for Urban Studies, on “The Harder We Run: The State of Black Buffalo in 1990 and the Present,” a 2021 report to the Buffalo Center for Health Equity.

The Harder We Run: The State of Black Buffalo in 1990 and the Present

By Henry-Louis Taylor, Jr., Jin-Kyu Jung, and Evan Dash

The U.B. Center for Urban Studies is releasing its study, The Harder We Run: The State of Black Buffalo in 1990 and the Present, by Henry-Louis Taylor, Jr., Jin-Kyu Jung, and Evan Dash. Thirty-one years ago, in 1990, the U.B. Center released its study, African Americans and the Rise of Buffalo’s Post-Industrial City, 1940 to Present. This investigation was the most comprehensive study ever conducted on Black Buffalo. This past summer, the Buffalo Health Equity Center asked the U.B. Center to use the 1990 Black Buffalo Study and answer the question, “Has Black Buffalo progressed since 1990?” The U.B. Center took on the project but did not request any funding. The report, The Harder We Run, answers the question, “Has Black Buffalo progressed since 1990?” The report tells us what happened to Black Buffalo over the past thirty-one years, why it happened, and what we can do about it.

TaylorHL The Harder We Run

Another Voice: News editorial glosses over racist history of Route 33

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

There’s an important petition up at change.org started by University of Arizona Assistant Professor Erika Gault, who grew up in Buffalo. It concerns Mayor Byron Brown’s reluctance to publicly say the name of mayoral candidate India Walton, and the recent replay in Buffalo of historically racist tropes concerning Black women.

I, too, would like to recognize the elision of proper names, albeit in a somewhat adjacent sphere: The Buffalo News editorial board’s opinion regarding the renewed energy around doing away with the Kensington Expressway (“Push to bury Route 33,”May 23).

UB reinstitutes indoor mask mandate effective Tuesday

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

The University at Buffalo will reinstate its indoor mask mandate beginning Tuesday for all employees and students regardless of their vaccination status, the school said Monday.

The mask rule is expected to remain in place when students return en masse later this month.

Vaccine update: 9 charts that show how New York is handling the spread of COVID-19

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

How have case numbers changed over time? How many people have been vaccinated? Find out with these charts and maps, updated weekly.

Economy update: 6 charts that show how the economy is performing in Buffalo and New York

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

See how unemployment has changed over time, plus how small businesses are doing in our community, and more economic indicators with these regularly updated charts and graphs.

UB to celebrate 2020 graduates in fall commencement ceremony

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

UB President Satish K. Tripathi on Friday announced that the university will host in-person commencement exercises for members of the Class of 2020 in the fall, nearly a year and a half after they were supposed to be feted.

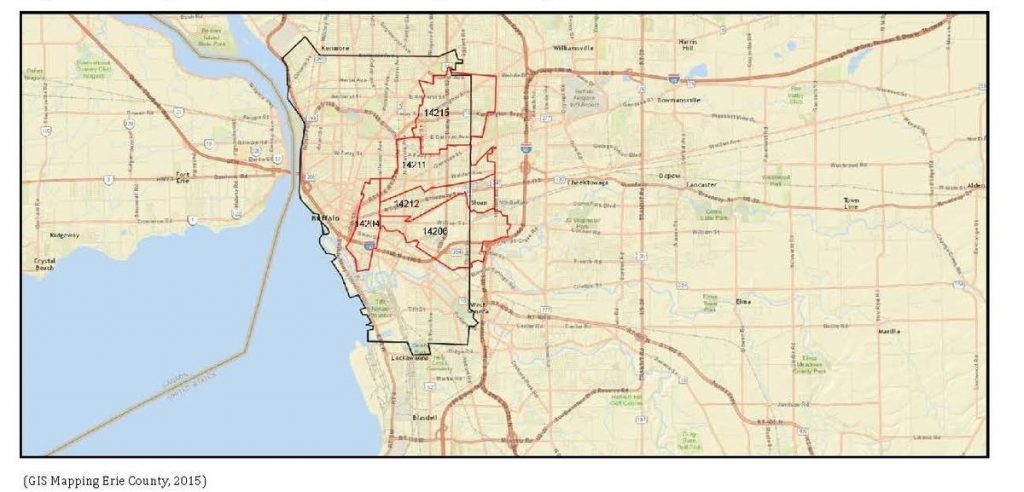

Buffalo’s 14215 ZIP code among those Cuomo targets for vaccine push

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

With roughly one in four New Yorkers still unvaccinated against Covid-19, Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Monday said the state will attempt to boost the vaccination rate by targeting 117 ZIP codes that have both low vaccination rates and a high spread of Covid with outreach efforts by community-based organizations.

Twenty-five of those ZIP codes are outside New York City and Long Island and include two in Western New York: 14215 in Buffalo and Cheektowaga and 14770 along the Pennsylvania border in Cattaraugus County.

Can Erie County office close the health equity gap?

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

Erie County Executive Mark Poloncarz plans to spend $300,000 in federal stimulus money to attack the racial disparity in health outcomes. It’s a good start. The challenge for Poloncarz: Ensure the spending actually narrows the gap.

In Erie County, African American children are more than twice as likely to die within a year after birth, according to the County Health Rankings report, and twice as likely to die before they turn 18. African American girls are 2 1/2 times more likely than whites to give birth in their late teens.

Underlying all of that is poverty. Nearly half of African American children in Erie County are living in poverty – five times the rate among white children.

Lottery for $500 monthly checks part of proposal for Buffalo’s stimulus spending

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

“That’s a joke: $500 for 1,600 families that are probably making about $15,000 or $16,000 dollars a year?” Taylor said.

Some 68% of African-American residents in the city are renters, along with about 78% of the Latino population and 62% of the Asian-American community, he said, citing census figures.

“These families are faced with two issues: They’re paying 40, 50, 60% of their income on housing, and … many of these families, especially those who don’t own a car, have almost no money left over to do anything with,” Taylor said.

Lynne Dixon’s 25-point plan launches county comptroller contest

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

The 25-point proposal, to be released today, revolves around “helping senior citizens, small businesses, and taxpayers,” her campaign said. Her “signature item,” she added, is allowing senior citizens on a fixed income and small business owners to pay property taxes monthly, instead of annually.

Buffalo police community outreach

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

The Buffalo Police Department held a community outreach called Taking It to the Streets at New Hope Baptist Church, across from Schiller Park, Tuesday, July 20, 2021. It provided a chance for the police to interact with the public. Police officials and various officers were on hand as well as community groups and services. They plan on doing similar events around the city throughout the rest of the summer.

Buffalo Residents Protest in Solidarity with Cubans

Read the full article from WKBW Buffalo here.

Thousands took the streets in Cuba last week to protest against the government. In Buffalo on Sunday around 50 residents took to the streets to march in solidarity.

Erie County looks at new way to tackle old problem: serious health disparities

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

While Covid-19 drew renewed attention to the local health disparities issue, the nature of the disparity has been known for a long time. Erie County fares worse on many state and national averages when it comes to premature deaths, lack of preventative care and childhood poverty among African American residents.

David Robinson: Buffalo Niagara worker shortage slows the Covid-19 recovery

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

That’s worrisome because it’s a sign that the low-hanging fruit in the recovery has been pretty much picked. And we’re still down about 30,000 jobs from where we were in June 2019, so the recovery is far from over.

Now that the economy is operating without many Covid-19-related restrictions, it is the more difficult structural issues that are holding back the recovery.

Buffalo’s last school zone speed camera shut off

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

After at least two lawsuits, accusations of a money grab by the city and more than a year of conflict between the Common Council and Mayor Byron W. Brown, the last school zone speed camera in Buffalo has been turned off.

The move followed what Brown described as a “passionate plea” from University Council Member Rasheed N.C. Wyatt in a Facebook post Thursday.

Brown commits to mayoral debate co-sponsored by The Buffalo News

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

Buffalo Mayor Byron W. Brown has committed to participating in a debate against his opponent in the mayoral race, Democratic Party nominee India B. Walton, in an event being sponsored by The Buffalo News, WGRZ and Buffalo Toronto Public Media.

Walton, who defeated Brown in the Democratic primary, was out of town, and her campaign has not yet committed to participating in the 7 p.m. Oct. 12 debate.

Citizen panel questions Buffalo police chief on white supremacy in policing

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

Noting a series of alarming incidents around the country, members of a citizens police oversight panel that reports to the Buffalo Common Council on Wednesday questioned Police Commissioner Byron C. Lockwood on the steps being taken to prevent a white supremacist from infiltrating the department’s ranks.

Council sets meeting for public to weigh in on federal stimulus spending

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

Buffalo is slated to receive $331 million in federal stimulus funding. Half of the windfall arrived last month. The second payment is expected to come next year. All of the funds must be spent within the next four years. The Common Council will hold a public meeting for the community to weigh in on the spending.

‘Supply is not the issue’: Why rural places like Allegany County lag in vaccinations

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

The vaccination campaign is running up against the independence prized in rural areas, vaccine hesitancy, lingering animosity over the governor’s public health restrictions and the continuing spread of misinformation about Covid-19. Those and other factors have contributed to the low vaccination rate in Allegany and elsewhere, experts say.

Professionals from city’s wealthier areas powered India Walton to victory

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

Walton grew up poor in one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, but she beat Buffalo’s four-term mayor, Byron W. Brown, with votes – and a lot of campaign help – from professionals in the city’s wealthier enclaves. And now Walton and her supporters are working to defeat Brown’s write-in bid in November and create a progressive city administration led by a self-proclaimed democratic socialist.

Six Takeaways From India Walton’s Historic Victory in Buffalo

Read the full article from Jacobin here.

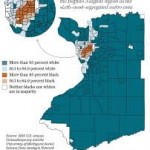

As clichéd as it sounds, Buffalo’s historic June 2021 primary, in which democratic socialist India Walton won a major upset over four-term incumbent Byron Brown, is something of a tale of two cities. And it’s the same tale that Buffalonians have discussed for generations: the “East-West divide” carved by Main Street through the heart of the city.

At Albright-Knox, steel frame for expansion is in place: ‘This is a remarkable moment’

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

The expanded museum, at a cost of $168 million, is expected to reopen in fall 2022, three years since the museum closed in November 2019. When it reopens, the museum will become known as the Buffalo AKG Art Museum. AKG stands for the museum’s major contributors: John J. Albright, Seymour H. Knox Jr. and Jeffrey E. Gundlach.

Masks no longer required in summer school

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

The state Health Department updated the guidance because of the “current low rates of Covid-19 transmission,” it said in an email to school districts.

Schools and districts may implement the masking policies for child care, day camp and overnight camp programs, the state said. That guidance says that unvaccinated children “are strongly encouraged but not required to wear face coverings indoors as feasible.”

India Walton’s mayoral campaign reinforces progressive police proposals

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

Walton cruised to victory last month by emphasizing new ways to solve old problems, especially in policing. She reiterated on Wednesday her plan to reallocate $7.5 million of the Police Department budget to programs that link usual subjects of police attention to mental health services. Her Wednesday event also marked the first of many in which she is expected to highlight her proposals, backed by high-profile figures like Williams. Others with similar socialist philosophies – such as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of the Bronx and Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont – are mentioned as other potential campaign allies.

Erie County legislators expect ugly fight before vote on how to spend stimulus money

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

The Democratic majority of the Erie County Legislature stands poised to approve County Executive Mark Poloncarz’s $123.7 million spending plan Thursday, which would take one of the biggest windfalls in decades and use it to boost a variety of infrastructure and community improvement projects, as well as county payroll.

But the Republican-supported minority caucus is gearing up to wage a battle on the Legislature floor. They will push to sidetrack the county executive’s spending plan and replace it with a different plan that they say offers more public input.

Buffalo offering aid for those behind on water bills

Read the full article from WKBW Buffalo here.

The City of Buffalo and the Buffalo Sewer Authority are providing relief to the more than 30,000 households that fell behind on water and sewer bills during the past 16 months. Of the $361 million the city received through the American Rescue Plan, $13 million of it will be used to wash away debt for low-income families who faced financial hardships as a result of the pandemic.

Over 1,100 vaccinated at home, but Erie County program hits snags

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

Erie County Executive Mark Poloncarz first announced on May 11 that the county had contracted with Buffalo Homecare and the Visiting Nursing Association of Western New York to deliver and administer the vaccine to the homes of eligible residents who request it, regardless of whether they are homebound.

After a year of pandemic learning, a more expansive approach to summer school

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

At least 20% of federal American Rescue Plan money must be used in the next three years to deal with learning loss by students due to the Covid-19 pandemic. That amounts to $63 million in Erie and Niagara counties, and for many school districts, summer school will be one of their tools.

As the fall campaign begins, India Walton confronts questions over her past

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

A self-proclaimed democratic socialist who vows to “put people first,” she said her life – growing up poor on the East Side, being a single mother of four boys, being a nurse and a community organizer and having firsthand experience being arrested by Buffalo police – has prepared her for this moment as she faces a write-in campaign from an emboldened Brown in the general election on Nov. 2.

What the primary vote tells us

Read the full article from Investigate Post here.

Ken Kruly is a political analyst for WGRZ-TV, publisher of Politics and Other Stuff and author of Money In Politics for Investigative Post. In an analysis for Investigative Post, Kruly compared Brown’s performance this year to the results of his previous four mayoral campaigns. He found Brown’s share of the vote dropped in six of the nine Common Council districts compared to four years ago.

How India Walton would revamp policing in Buffalo

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

“She will prioritize addressing the root causes of crime such as concentrated poverty and lack of living-wage jobs,” according to her platform on her campaign website, and she would emphasize “harm reduction and restorative justice programs rather than punitive measures.”

How Did a Socialist Triumph in Buffalo?

Read the full article from The New York Times here.

That danger is real. Polls reveal that both Black and white voters reject the slogan “Defund the police.” Yet Walton has shown that even in a city where shootings have surged a staggering 116 percent so far this year, a socialist promising police reform can win.

Byron Brown launches write-in campaign for mayor as others eye the race

Read the full article here.

Gone was the aloof incumbent seemingly self-assured of an unprecedented fifth term leading Buffalo. Instead, Brown launched a “do over” candidacy, passionately announcing in the Statler Terrace Room a write-in campaign for the Nov. 2 general election to reclaim the office he preliminarily lost to newcomer India B. Walton on June 22.

Walton’s campaign outworked Brown

Read the full aricle here.

She’d beaten Brown by 1,507 votes, according to the unofficial tally by the Erie County Board of Elections. That’s more than the absentee ballots left to be counted. She won almost 52 percent of the vote to Brown’s 45 percent. Le’Candice Durham, a City Hall employee whose campaign seemed designed to siphon votes from Walton to benefit Brown, got 650 votes, or just over 3 percent.

Council seeks judge’s opinion on legislation to eliminate school speed zone cameras

Read the full article from Buffalo News, here.

Buffalo Mayor Byron W. Brown has said he will not sign expedited legislation approved by the Common Council to eliminate school zone speed cameras because council members did not follow the proper process.

Mayor Brown didn’t budget money for speed zone cameras – but he’s not giving up on them

Read the full article from Buffalo News, here.

Buffalo Mayor Byron W. Brown did not include any revenue from school zone speed cameras in his 2021-22 budget proposal.

State AG says Buffalo can establish a civilian review board

Read the full article from The Buffalo News here.

“Buffalo can take steps now to establish a civilian review board to investigate allegations of police misconduct, according to the New York State Attorney General’s Office. Such a board should hold final disciplinary authority over officers and subpoena power, and it should have a substantial budget and a qualified professional staff to carry out its duties, according to a letter from the office’s Civil Rights Bureau to Mayor Byron W. Brown.”

Faculty weigh in on Chauvin verdict, fight for equality

Read the full article from UBNow here.

“This victory reflected the people’s power. It was made possible by the millions who drew a line in the sand and said ‘enough.’ But history teaches us, the retrogressive forces in this country will resist. Even as they say, ‘justice was served, and this is the beginning of a new beginning,’ they will block efforts to defund the police and recreate policing as we know it. These same forces will fight reforms to improve the quality of neighborhood life among Blacks, Indigenous and people of color. They will work tirelessly to maintain the status quo. And the fightback will continue. The people will build on this ‘shining moment.’ The people will continue to the quest for that day when BIPOC will cry ‘free at last, free at last.’ This victory will cause them to keep the faith and raise the battle cry, ‘Remember George Floyd. Power to the People.’”

Sheriff’s candidate: Party chairman said she’s ‘not what a sheriff looks like’

Read the full article from The Buffalo News here.

“Kimberly L. Beaty has more than 30 years in law enforcement and believes she has credentials to make a strong push for the Erie County sheriff’s seat as former deputy commissioner for the Buffalo Police Department. But according to her recount of conversations with the Erie County Democratic Party chairman, there was one thing Beaty didn’t have. The right look. ‘He said, “You’re not what a sheriff looks like, and what people are used to,” ‘ she recalled.”

Buffalo’s school zone speed cameras are on a path to being removed

Read the full article from The Buffalo News here.

“Six out of nine city lawmakers voted Tuesday to get rid of Buffalo’s school zone speed cameras by September, but it is not a done deal. Their patience is running out.…According to the City Charter, Mayor Byron W. Brown has 10 days to sign the legislation or veto it. If he vetoes it, the legislation goes back to the Council, which then has 30 days to vote to override the veto. If Brown does not act then, the legislation becomes law.”

New UB website aims to help reverse health inequities in Buffalo

Read the full article from UBNow here.

“‘The partnership between the task force and the Community Health Equity Research Institute was instrumental in partially mitigating the deadly impact of the pandemic in communities of color in Buffalo,’ Murphy says. The vision of the website was guided chiefly by contributions from three members of the institute’s Steering Committee: Henry Louis Taylor Jr., professor of urban and regional planning, School of Architecture and Planning, and associate director of the institute; Kelly Wofford, community engagement coordinator in UB’s Center for Nursing Research in the School of Nursing; and Christopher St. Vil, assistant professor in the School of Social Work.”

Marijuana legalization in NY to lead to automatic expungement of some drug convictions

Read the full article from Democrat and Chronicle here.

“Henry Louis Taylor Jr., director of the University at Buffalo Center for Urban Studies,said expungement ‘begins to close the road from the neighborhood to the jail.’ But to create substantive change, he said, the funding set aside in the legislation must include connecting people who were incarcerated to job opportunities and other resources, as well as repairing harms done to communities by marijuana prohibition.The changes, he said, that need to come from funding have to be transformative and may include items such as housing subsidies for communities and cooperatives.Importantly,he said, the community should have a say in how the money is spent.”

Race and multicultural experts and area residents weigh-in on Rob Lederman’s use of a racial slur

Read the full story from WIVB here.

“Experts say the racial slur is meant to describe people who are mixed race and it dates back to slavery and the practice of raping female slaves. ‘Rape was institutionalized, and it meant that women were the plaything of the plantation owner to be taken whenever he chose to. As I always say, when I look in the mirror I see the color of rape,’ said Henry Louis Taylor Jr., UB director of the university’s Center for urban studies. ‘It’s a reminder of a time when African American women had no control over their bodies.'”

Brown calls for a more focused citizens’ rights commission to improve policing

Read the full article from The Buffalo News here.

“The report calls for the city’s Commission on Citizens’ Rights and Community Relations to undergo a community planning process with residents from all neighborhoods to improve interactions with the police. The plan also calls on the commission to provide a survey on its website for residents to complete any time they interact with police officers.”

New Buffalo program seeks to replace dilapidated houses with new homes

Read the full article from The Buffalo News here.

“Buffalo kicked off a pilot program Tuesday with the demolition of a dilapidated house in the Hamlin Park neighborhood to make way for a new house to be built within 12 months…The program seeks to replace vacant, blighted structures with affordable houses for new homeowners. The city’s Division of Real Estate identifies a community housing partner for construction of a new home within 12 months from the date of demolition.”

State sues Sheriff Howard over handling of sexual misconduct allegations in county jails

Read the full story from The Buffalo News here.

“‘The Erie County Sheriff’s Office has an abysmal track record of complying with the requirement to notify the commission of incidents that jeopardize the safety and well-being of individuals in custody, facility staff and the community,’ Commission of Correction Chairman Allen Riley said in the written statement.

Probe faults mayor, former police chief for keeping Prude death secret

Read the full article from NBCBLK here.

“An investigation into the official response to Daniel Prude’s police suffocation death last year in Rochester, New York, is faulting the city’s mayor and former police chief for keeping critical details of the case secret for months and lying to the public about what they knew. The report, commissioned by Rochester’s city council and made public Friday, said Mayor Lovely Warren lied at a September press conference when she said it wasn’t until August that she learned officers had physically restrained Prude during the March 23, 2020, arrest that led to his death.”

Black Lives Matter backs Amazon union push in Alabama

Read the full article from AP News here.

“‘Black workers have historically been the backbone of this country, its institutions, and innovations,’ said Patrisse Cullors, the executive director of Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation, in a statement. ‘Therefore, it is fully within our rights and dignity that we be treated and compensated fairly. Just as we have the right to live, we also have the right to work.'”

Dynamic student + committed med school = real progress on equity

Read the full article from The Buffalo News here.

“Collier credits the medical school’s interdisciplinary Health in the Neighborhood course taught by instructors including Henry L. Taylor Jr., director of UB’s Center for Urban Studies, and the Rev. Kinzer M. Pointer of the African American Health Equity Task Force…She ticked off a number of such social and economic issues that can impact health: redlining, older homes with lead paint, transportation inequities that make it hard to seek care, living in a food desert or a neighborhood that makes it impractical to exercise. ‘You can’t say to a person, “Go run outside” if they don’t have sidewalks,’ Collier said.”

Racial disparities plague vaccine rollout in WNY and across U.S.

Read the full article from The Buffalo News here.

“In New York, white residents have received a disproportionate share of vaccines in each of the state’s 10 regions and in all five counties of Western New York. That disparity is especially dramatic in Erie County: While white residents make up just over 81% of the population, they account for almost 91% of the newly vaccinated. Black residents, on the other hand, represent 5.7% of all vaccinated people (compared to 13.1% of the population), while Asian residents make up 2.5% of those vaccinated (3.6% of the population) and Hispanic residents make up 2.2% (4.5% of the population).”

Fruit Belt housing project delayed to allow community talks

Read the full article from The Buffalo News here.

“The nonprofit developers proposing 50 units of affordable housing in Buffalo’s Fruit Belt neighborhood asked the Buffalo Planning Board to delay consideration of the project for another month, as they reach out to the community to resolve concerns and resistance. Dunkirk-based Southern Tier Environments for Living and the Fruit Belt Community Land Trust want to construct a 33-unit apartment building at 326 High St., at the corner of Peach Street, along with five three-bedroom duplexes, one two-bedroom duplex and five single-family homes on scattered sites.”

Will the Current Focus on Black Lives Matter Lead To Lasting Change?

Read the full article from Diverse Issues in Education here.

“Every sphere — academe, government, business, sports, religion, legal, etcetera — ‘must commit to changing the way they look and function,’ Dr. Lori Martin, interim director of Louisiana State University’s African and African American Studies Program, told Diverse via email. ‘They must be prepared to disrupt and dismantle the policies and practices that perpetuate anti-Black sentiments and demonstrate a commitment that is lifelong.'”

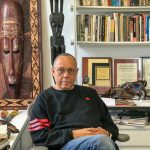

Henry Taylor is a tireless advocate for racial justice through urban planning

Read the full article on the UB School of Architecture and Planning website here.

“As an advocate for centering the work of black heterogeneous communities, [Taylor] urges planners to delve into the mundane, the day-to-day realities of a single mother raising two children, and the varying challenges of multi-generational Black households. In the context of the pandemic and the fight against health disparities he plays a pivotal role as associate director of The Community Health Equity Research Institute, which brings UB faculty members and community leaders in Buffalo to address the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on communities of color.”

Daniel Prude’s Death Leads to No Charges for Police

Read the full article from The New York Times here.

“‘The criminal justice system has demonstrated an unwillingness to hold law enforcement officers accountable in the unjustified killing of unarmed African-Americans,’ [Attorney General] James said, her voice growing emotional at a news conference at Aenon Missionary Baptist Church in Rochester. ‘What binds these cases is the tragic loss of life in circumstances in which the death could be avoided.'”

Rachel Lindsay Discusses Chris Harrison’s Apology and ‘Explicit’ Versus ‘Implicit’ Racism

Read the full article from Parade here.

Being aware that implicit racism exists is crucial, Dr. Taylor says. But, he adds, it’s also important for people to “engage in a lot of self-education.” “I think every white person should have a book on Blacks and Latinx that they read,” Dr. Taylor says. He specifically cites the book, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, as a good option. Dr. Taylor also urges businesses and schools to host workshops on the issues of racism and bias. “The level of awareness about these kinds of issues is terrible,” he says.

Opponents: School zone speed cameras target ‘Buffalo’s most impoverished residents’

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

“‘We can find no evidence that these speed zone cameras are saving people’s lives, making life safer and making the world better for the children anywhere, not just here in Buffalo. There’s no data to support that. But what there is data to support … revenue generation,’ Taylor said. ‘It’s nothing more than a revenue grabbing scheme … designed to bilk the African American community from resources.'”

Surgery launches anti-racism, health care equity initiative with West lecture

Read the full article from UBNow here.

“Cornel West, Harvard University professor, bestselling author, political activist and public intellectual, will speak via Zoom at “Beyond the Knife,” the initiative’s first public event, from 4-5 p.m. on Feb. 18. This event is free and open to the public. Register and submit questions for the question-and-answer session online.”

Buffalo-made ‘The Blackness Project,’ now on Amazon Prime, keeps dialogue open on race relations

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

“University at Buffalo professor Henry Louis Taylor Jr., who narrates the film, contributes considerably to the documentary. Taylor rivetingly condemns Americans’ fateful choice after the Civil War to support ex-Confederates’ interests rather than build up Black Americans’ opportunities, and provides a poignant concluding call to pursue social justice.”

Black Lives Matter movement nominated for Nobel peace prize

Read the full article from The Guardian here.

“The Black Lives Matter movement has been nominated for the 2021 Nobel peace prize for the way its call for systemic change has spread around the world. In his nomination papers, the Norwegian MP Petter Eide said the movement had forced countries outside the US to grapple with racism within their own societies. ‘I find that one of the key challenges we have seen in America, but also in Europe and Asia, is the kind of increasing conflict based on inequality,’ Eide said. ‘Black Lives Matter has become a very important worldwide movement to fight racial injustice.’”

Crumbling Investments: Effort by city to revitalize Homewood has resulted in lingering neglect and frustration

Read the full article from Pittsburgh-Post Gazette here.

“‘In this case, I would argue that the city is a slumlord that is consciously participating in the underdevelopment of the community,’ said Henry Louis Taylor Jr., a professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning and associate director of the Community Health Equity Research Institute at the University of Buffalo.”

Antoine Thompson Q&A: Promoting Housing in Democracy with the National Association of Real Estate Brokers

Read the full article from MGIC Connects here.

“‘Looking back, who served as role models to you, and what did you learn from them?‘ ‘One of my role models is Dr. Henry Taylor, director of the UB Center of Urban Studies, because of his strong commitment to urban policy and his advocacy for building civic capacity to effect community change. Another is R. Donahue Peebles, who inspires me because of his success in real estate and his understanding of the role of politics in development and building wealth.'”

A snapshot of Homewood history

Read the full article from Pittsburgh Post-Gazette here.

“Henry Louis Taylor, Jr., whose research at the University of Buffalo focuses on distressed urban neighborhoods and the health of those who live there, said the trajectory of Homewood follows a familiar pattern. ‘In American cities and suburbs, the way you increase residential land value under the current system in the country [is] as whiteness and social-class exclusivity increases, values go up. As Blackness and people of color increase and social inclusivity increases, values go down,’ he said.”

Cuomo: Black hospital workers shunning vaccine at greater rate than whites, Latinos

Read the full article from Buffalo News here.

“The governor said there’s ‘understandable’ cynicism and distrust of the health care system in the Black community because of previous injustices. But the governor said such distrust isn’t justified when it comes to the Covid-19 vaccine. He said he has been calling pastors and other leaders in African American communities around the state about it, and the state plans to roll out an advertising campaign aimed at building trust in the vaccine among Black New Yorkers.”

Rochester Police Pepper-Sprayed 9-Year-Old Girl, Footage Shows

Read the full article from The New York Times here.

“The police department in Rochester, N.Y., released body-camera footage on Sunday that showed a 9-year-old girl being handcuffed and pepper-sprayed by police officers who had responded to a family disturbance call. During the incident, which occurred Friday afternoon, officers restrained the girl, pushing her into the snow in order to handcuff her, while she screamed repeatedly for her father, the footage showed. At one point, an officer said, ‘You’re acting like a child.’ She responded, ‘I am a child.'”

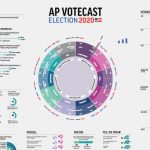

UB experts believe there’s a fundamental flaw with current polling

Read the full article from WBEN here.

BUFFALO (WBEN) – “The one thing we can say for sure in this is that the big loser last night was the pollsters,” said Professor Jim Campbell, as a group of University at Buffalo experts held a virtual meeting to discuss Election Night and the election process as a whole.

“This was not supposed to be as close as it turned out to be in many states,” he continued.

Wisconsin turned out to be a very thin margin, as election officials continues to tally votes in a state where Democratic Nominee Joe Biden holds a lead. Prior to Tuesday night, it was anticipated that Biden would run away with Wisconsin, holding nearly a double-digit lead in some polls.

UB Professors Discuss Divisions Amid Presidential Election

Watch the video and read the full article from Spectrum News here.

“This is a deeply, deeply divided country along ideological lines,” said Henry Louis Taylor, professor of urban planning.

“This was in some ways a referendum on President Trump and indicates how sharply polarized we are as a nation,” said James Campbell, professor of political science.

President Trump has threatened lawsuits to come over the voting process and collecting and counting of ballots in some states.

Election law expert James Gardner expects to see recounts and court cases to resolve this, but also wondered about the how the federal courts, including the United States Supreme Court, would handle the situation with objectivity.

Is Erie County turning red?

Watch the video and read the full article from WKBW here.

“Call it a ‘post game breakdown’ of the 2020 election in Western New York by professors at the University at Buffalo.

The question – is traditionally blue Erie County becoming republican country?…

Professor Taylor says the Trump administration has caused a deep divide and that reveals far reaching racism.

‘This is Donald Trump’s America,’ Taylor stated.

Taylor also stated that he believes democrats have ‘no vision that excites people.'”

Confronting the Causes of Residential and School Segregation

Read the full article from Housing Matters here.

“Evidence shows that government housing policies and individual practices created and sustain segregation between white and Black people and that segregation exacerbates racial wealth inequality, racial achievement gaps, and racial profiling. This 2017 study applies a “white racial frame” to explain the persistence of residential and school segregation, synthesizing more than 60 articles from the fields of sociology, economics, critical theory, and law. The authors’ frame reflects the theory that white people who hold power in the US purposefully maintain their dominance and perpetuate socioeconomic inequities based on race and ethnicity. By applying this frame, the authors shift focus from disparate outcomes by race and ethnicity to the (often white) lenders, police, educators, and politicians who shape structures of opportunity.”

UB-community partnership reducing COVID-19 deaths among African Americans

Read the full article from WGRZ, here.

“The fact that this community-university partnership was able to mitigate the high mortality among African Americans in the first wave puts us in a position to build on that achievement during this coming flu season and a possible second wave,” said Tim Murphy, MD, SUNY Distinguished Professor in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB and director of the Community Health Equity Research Institute and UB’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute “And it’s something that can be replicated in other communities.”

Black Man Died of Suffocation After Officers Put Hood on Him

Read the full article from The New York Times, here.

“A Black man died of suffocation in Rochester, N.Y., after police officers who were taking him into custody put a hood over his head and then pressed his face into the pavement for two minutes, according to video and records released by his family and local activists on Wednesday. The man, Daniel Prude, 41, died on March 30, seven days after his encounter with the police, after being removed from life support, his family said.”

Experts say Trump’s eviction moratorium is hard to access and will be of limited help

Read the full article from Salon, here.

“‘Without rent forgiveness, tenants will ultimately have to pay back rent along with any late-fees and penalties, or face eviction when the moratorium is lifted,’ Silverman explained. ‘It is ultimately up to landlords to decide if they are going to pursue eviction, but at some point in the future, we can anticipate that there will be a spike in evictions across the country. It could be very destabilizing to the economy at the very time that the COVID crisis ends. For renters, it will also have ripple effects on their credit history and ability to find replacement housing.'”

St. Louis couple who aimed guns at protesters makes false convention claim about Joe Biden, suburbs

Read the full article from PolitiFact, here.

“A Republican National Convention speaker falsely claimed that the Democratic Party under Joe Biden would ‘abolish the suburbs altogether by ending single-family zoning.’ That’s not true. The claim came from Patricia McCloskey, a St. Louis lawyer who, along with her husband, Mark, is facing felony charges for pointing guns at protesters marching outside their home…’This is a red herring, pure and simple,’ said Robert Silverman, a professor or urban and regional planning at the University of Buffalo. ‘Zoning is a local function in the United States, and the suggestions made in the McCloskeys’ speech are patently false.'”

Black Americans Still Face Obstacles In Obtaining Credit, Mortgage Loans

Read the full article from International Business Times, here.

“Black Americans are denied access to credit far more than their white counterparts, according to a recent report from LendingTree (TREE), the online lending marketplace. Specifically, regardless of income levels, in 2019, Black adults were denied credit – including credit cards, higher credit card limits, mortgages, refinancing, student loans, personal loans – 44% of the time (versus 19% for whites). Put another way, Blacks were denied or approved for less than the amount requested 57% of the time versus 24% for whites.”

Black Workers in Buffalo Face Bigger Share of Coronavirus Impact

Read the full article from Wall Street Journal, here.

“The coronavirus pandemic risks widening the financial gap in Buffalo, N.Y., between white and Black workers, who entered this year’s economic downturn with less financial security and are disproportionately employed in sectors more vulnerable to layoffs and exposure to Covid-19. Over the last half-century, Black people in Buffalo were more likely to trade relatively stable manufacturing jobs for lower-wage work in the service sector, live in poorer neighborhoods and face higher levels of unemployment, according to researchers…”

UB strips Fillmore, Putnam, Porter names from buildings, facilities

Read the full article from Buffalo News, here.

“Advocates for racial justice celebrated a decision by the University at Buffalo to strip the names of three historic figures from university buildings, facilities and roads because they supported slavery or promoted racist policies and values. ‘I think it’s a good move, and I think symbolism is important,’ said Henry Louis Taylor, a professor at UB’s Department of Urban and Regional Planning. ‘For the nation to deal with the issues of race in this country, we have to be honest about our history.'”

MFSA holds virtual discussion on race, racism at UB

Read the full article from UBNow, here.

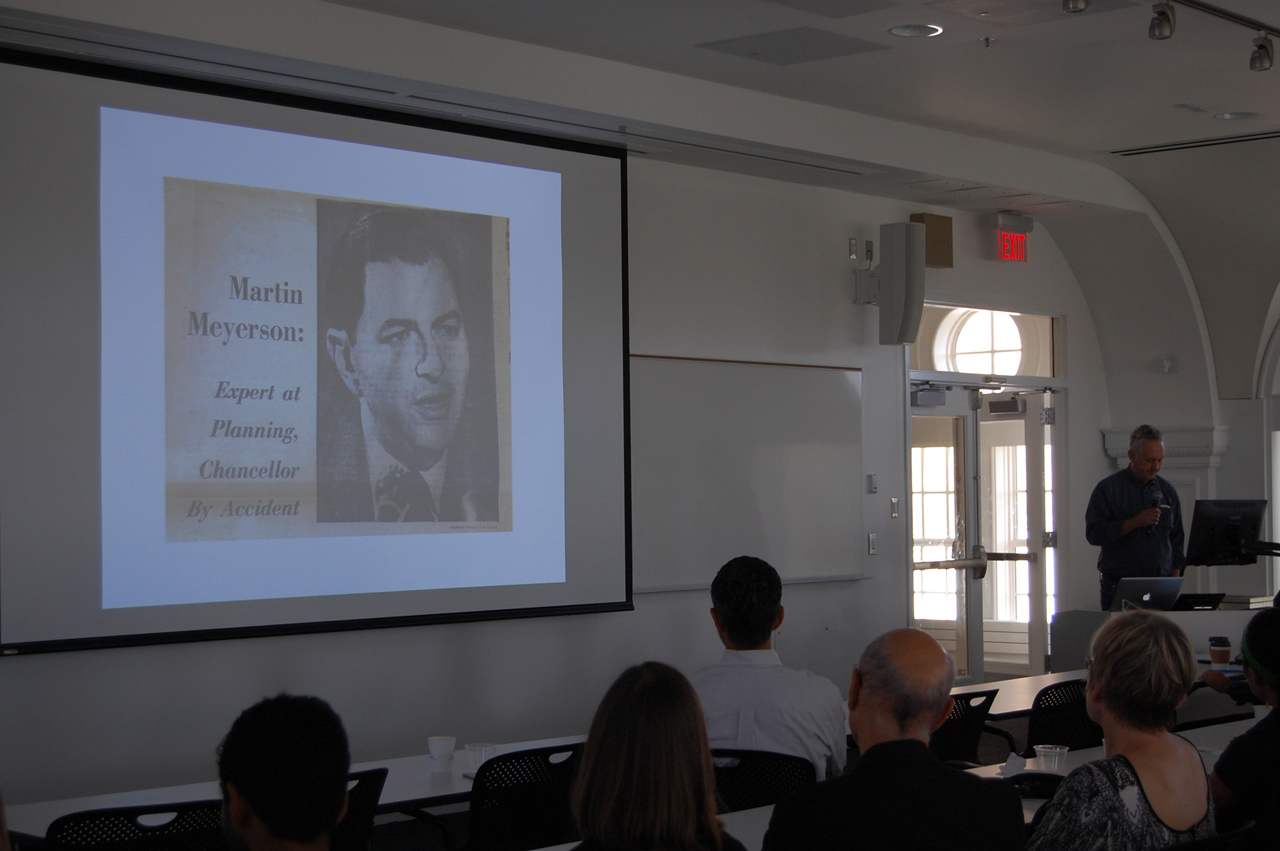

Henry Louis Taylor Jr., professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning and director of the Center for Urban Studies, outlined UB’s history in addressing racism on campus and in the community. From the late 1960s to the mid-1990s, UB built an infrastructure, including launching educational programs and hiring faculty members of color, to link UB to the Black community, he said.

But that infrastructure dwindled over the past two decades, a result of declining government support for public education, as well as flawed university efforts to address these issues, Taylor said. He called upon UB leadership to reinvest in these programs, and tackle race and racism in a more direct manner.

“I theorize that whenever race is not explicitly stated, whiteness becomes the default group, and people of color are pushed to the margins,” he said.

Those who were unable to attend the live event can watch it online.

Trump boasts of pushing low-income housing out of suburbs

Read the full article from Politico, here.

President Donald Trump is pining for support in the suburbs, and pushing out low-income housing is playing a part in his bid to get it.

In a set of tweets and in remarks in Texas on Wednesday, Trump bragged about his administration’s rescinding an Obama-era fair housing rule that was meant to combat housing discrimination. He characterized low-income housing as a detriment to the suburbs and claimed that Democrats were out to uproot and destroy suburbia — a cultural sphere that he equated to the American dream.

“You know the suburbs, people fight all of their lives to get into the suburbs and have a beautiful home,” Trump said during a talk in Midland, Texas. “There will be no more low-income housing forced into the suburbs. … It’s been going on for years. I’ve seen conflict for years. It’s been hell for suburbia.”

Urban planning as a tool of white supremacy – the other lesson from Minneapolis

Read the full article from The Conversation, here.

The legacy of structural racism in Minneapolis was laid bare to the world at the intersection of Chicago Avenue and East 38th Street, the location where George Floyd’s neck was pinned to the ground by a police officer’s knee. But it is also imprinted in streets, parks and neighborhoods across the city – the result of urban planning that utilized segregation as a tool of white supremacy.

Today, Minneapolis is seen to be one of the most liberal cities in the U.S. But if you scratch away the progressive veneer of the U.S.‘s most cyclable city, the city with the best park system and sixth-highest quality of life, you find what Kirsten Delegard, a Minneapolis historian, describes as “darker truths about the city.”

A reckoning: Reconsidering Millard Fillmore’s legacy

Read the full article from Buffalo News, here.

Millard Fillmore gets little love from presidential historians, but he’s enjoyed favorite son status in Buffalo for more than 150 years.

That’s beginning to change.

The 13th president lived here for years before and after his term in the White House. His fingerprints are on many educational and cultural institutions, from the University at Buffalo to Buffalo General Medical Center, and his name and image are sprinkled throughout greater Buffalo.

Now, Fillmore’s signing of the Compromise of 1850 – which included the loathsome Fugitive Slave Act – and his unsuccessful presidential run as a member of the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Know Nothing Party are raising questions about his lofty local status.

With faculty nudge, can UB lead on social justice?

Read the full article from Buffalo News, here.

A few years ago, University at Buffalo President Satish Tripathi used his annual address to trumpet the UB 2020 strategic plan as laying the groundwork for propelling Buffalo Niagara in everything from health care and the arts to business and industry.

But with that target year now here and bringing a whole new set of issues – or, rather, an acknowledgement of issues that Blacks have long tried to raise – UB’s faculty is pushing one of the region’s major institutions to take on something else: systemic racism.

In an overwhelming vote a couple of weeks ago, United University Professions – which represents most faculty – passed a resolution condemning “police violence against African American, Indigenous and Latino/Latina residents,” opposing “the militarization of police and its impact on communities of color and on peaceful protests,” and supporting “reallocation of Buffalo resources from policing toward investment in Buffalo’s low-income communities of color.”

Black applicants are more likely to be denied mortgages, study finds

Read the full article Marketplace, here.

Traditional measures of risk like debt-to-income ratios disproportionately hurt Black borrowers, said Henry Louis Taylor Jr., a professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Buffalo.

“They’re not going to do well on that because of the low incomes that they have traditionally and because of the debts that they acquire just trying to make ends meet,” he said.

‘UB Black faculty are disappointed with UB response to BLM movement’

Read the full article from The Spectrum, here.

UB Professor Henry Louis Taylor, Jr., who has spent decades studying and writing about inequality, called the UB responses “just short of pathetic.”

Taylor, a professor in the department of Urban and Regional Planning, believes Foster’s letter was “right on target.” He and Foster are both executive members of the SUNY Black faculty group.

“I think it shows absolutely no understanding of the challenges that we face at this moment in time and they just oughta stop and give this to somebody that knows what they’re doing or talk to somebody that knows what they’re doing because it’s been pathetic,” Taylor said. “You know, this university has been backsliding in a lot of areas as it relates to race and class.”

Buffalo’s Police Brutality Didn’t Start With Martin Gugino

Read the full article from The Nation, here.

According to activists circulating a petition demanding his immediate resignation, [Mayor] Brown has never demonstrated an inclination to change the way police operate.

In fact, those activists say, the opposite is true. Under three police commissioners named by Brown in his 14 years as mayor, the department has instituted policies embodying the specific brand of racism that fuels protests across the country.

Some examples:

§ Setting up police checkpoints in poor, mostly black and Latino neighborhoods, which were discontinued after their constitutionality was challenged in a lawsuit.

§ Raising revenue for Brown’s cash-strapped administration by targeting motorists in those same neighborhoods for minor infractions—busted headlights, expired registrations or insurance cards, rolling stops.

§ Creating special units with a reputation for brutality and disregard for the Fourth Amendment.

‘It was never just about Floyd’: Protests reflect anger over inequality, neglect

Read the full article from Buffalo News, here.

“Taylor, of the Center for Urban Studies, said he does see hope for structural change this time, of the type that Buffalo’s black community didn’t get in 1967. A broad, diverse coalition of activists has mobilized around Buffalo’s inequities, he said: not only in the criminal justice system, but in neighborhood development, housing and education.”

“How Do We Get More Power?”

Read the full article from Open Society Foundations, here.

India Walton signed the lease: $1,200 a month for a modest, gut-renovated one-bedroom, $200 less than the listed price because she had her own appliances. Still, says Walton, “in this neighborhood? $1,200 was unheard of.”

At least it used to be. After decades of disinvestment and neglect, the Fruit Belt was beginning to boom.

The catalyst was right next door: a rapidly expanding medical complex, staffed by a growing number of doctors, nurses, and technicians looking for a nearby place to live.

In many ways, it was a familiar story: an African American neighborhood, long neglected by the city, suddenly deemed “desirable” and, in turn, overrun by new, more expensive development. But the story of the Fruit Belt, so named for the orchards planted there in the 1800s [PDF], went in an unexpected direction. As the medical campus grew, the small, sloping neighborhood sitting in its shadow—whose black population boomed following World War II—decided that its fate had not yet been sealed.

Mass Evictions Predicted as Short-Term Economic Relief Runs Out

Read the full article from Planetizen, here.

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr., a professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Buffalo, is featured in an ABC News article about the ongoing risk of mass evictions as the country’s millions of renters collides with tens of millions of new unemployment claims across the country.

Taylor said that “federal and statewide eviction moratoriums are based on COVID-19 timetables that are ‘too short’ and don’t consider predictions from medical experts that the pandemic could persist into the fall and beyond, as public health officials have suggested,” according to the article, written by Deena Zaru.

‘Mass evictions’ on the horizon as US confronts coronavirus housing crisis: Advocates

Read the full article from ABC News, here.

The first of the month is daunting for many low and middle-income Americans who will be struggling to pay their rent for the second time since the coronavirus pandemic essentially shut down the U.S. economy.

More than 30 million Americans have filed for unemployment insurance since the COVID-19 crisis hit the U.S. in March, and despite a range of temporary federal and state eviction moratoriums, some Americans are still being served eviction notices amid a public health crisis that requires many people to stay at home.

Henry Louis Taylor, Jr., a professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Buffalo, said that federal and statewide eviction moratoriums are based on COVID-19 timetables that are “too short” and don’t consider predictions from medical experts that the pandemic could persist into the fall and beyond, as public health officials have suggested.

NYC slashes program funding in ‘cautious’ FY21 budget

Read the full article from Smartcities Drive, here.

Dive Brief:

- New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the city’s budget for fiscal year 2021 (FY21), which previewed “cautious planning” and deep cuts across multiple sectors to address constraints amid the novel coronavirus pandemic. At $89.3 billion, the budget is $3.4 billion smaller than the one for fiscal year 2020 (FY20) to account for a potential $7.4 billion tax revenue loss across both years.

- The sanitation department, for instance, saw its e-waste and community composting subsidy programs temporarily disappear, amounting to cost savings of $3.4 million and $3.5 million, respectively in FY21 and beyond. The city also curtailed funding for its Summer Youth Employment Program; Vision Zero program; tree pruning and tree stump removal efforts; and educational district-charter partnerships program, among other adjustments.

- The budget aims to keep safety, health, shelter and access to food top of mind, but “Washington must also step up” to get New Yorkers through the pandemic, De Blasio said.

$8M will fund fight against Covid-19 in Buffalo’s most ‘vulnerable communities’

Read the full article from Buffalo News, here.

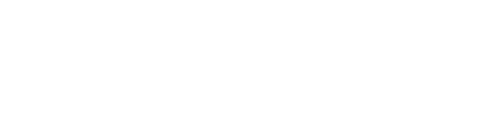

The plan comes after weeks of growing evidence that coronavirus has hit communities of color particularly hard, as well as vocal calls for governments and health care systems to step up more targeted interventions. Five of the seven Erie County ZIP codes with the highest concentration of Covid-19 are predominantly African American, according to an analysis by Alan Lesse, an associate dean at the University at Buffalo Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

Health department data also show black patients account for a disproportionate share of Erie County’s Covid-19 deaths.

“Black and brown people are scared. They’re staying home,” said Dr. Raul Vazquez, a physician and health care executive whose affiliated organizations serve thousands of low-income patients in Buffalo. “But the community will benefit from this. That’s very important.”

Black health experts say surgeon general’s comments reflect lack of awareness of black community

Read the full article from NBC News, here.

For Dr. Henry Louis Taylor, Jr., a University of Buffalo professor and researcher, there isn’t much of a controversy. The surgeon general missed the mark. And it’s not what he said, but what he did not say.

“It is irresponsible to talk about the elimination of drugs and alcohol without talking about eliminating the neighborhood-based social determinants that produce drug and alcohol abuse,” Taylor told NBC News.

The ‘step-up’ question does not reflect the realities of black America. It suggests that African Americans themselves are responsible for their plight.

“The Adams statement is, at best, irresponsible and, at worst, reflective of systemic structural racism,” Taylor added. “Black people live under enormous stress in places that are service deserts that lack gyms and are not suitable for jogging or even walking. At the same time, alcohol and tobacco companies target these communities. The ‘step-up’ question does not reflect the realities of black America. It suggests that African Americans themselves are responsible for their plight.”

Black Businesses Left Behind in Covid-19 Relief

Read the full article from CityLab, here.

Social distancing is not new to black communities. “Social distancing” in the form of anti-black segregation and discrimination was U.S. law throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. This created racial wealth disparities that have lingered, negatively impacting black people’s capacity to start and maintain businesses. The remnants of federally backed redlining practices, which financially isolated black people throughout the 20th century, throttled the amount of wealth black people could create from homeownership. Most entrepreneurs start businesses with the equity they’ve accrued in their homes. Consequently, black people, who’ve been over-burdened by American economic policies, require a different kind of stimulus in this coronavirus scourge era.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (Cares) package is an attempt to offset an impending recession caused by mandated and voluntary social distancing, which will last until at least April 30. Congress should also pass a relief package for people who’ve suffered from the de jure and de facto social distancing of racial segregation, which still sets African Americans apart from white people today on both a spatial and economic basis.

A Green Stimulus Plan for a Post-Coronavirus Economy

Read the full article from CityLab, here.

If we’re going to recover from the coronavirus pandemic, then let’s do it in a way that shakes up the status quo. This is the message that a group of U.S. economists, professors, and veterans of the last financial crisis sent in a letter to Congress yesterday asking for “green stimulus” legislation to jump-start the economy in a way that controls for climate change and poverty.

They are asking for a $2 trillion commitment for programs that will create living-wage jobs, amped-up public health and housing sectors, and a pivot away from a fossil-fuels-based energy frame. Under their plan, the stimulus would automatically renew every year at 4 percent of GDP, or $850 billion annually, as well as give the public more of a voice in whether — and how — large-scale corporations would get bailouts. For now, the coalition recognizes that the focus should be on stopping the spread of coronavirus and mitigating all related health risks.

How Coronavirus Affects Black People: Civil Rights Groups Call Out Racial Health Disparities

Read the full article from Newsone, here.

The president of Color Of Change, Rashad Robinson, explained:

“This pandemic reveals a terrifying reality — many Americans don’t even know if they are infected with COVID-19 because they are scared to go to the hospital and receive free tests and treatment that may saddle them with debt that could take years to pay off. After years of Republicans, big pharma and major corporations fighting against paid sick leave legislation and medicare for all we are left with a crisis where disproportionately Black low wage workers are continuing to support the public without the health insurance or paid time off that would make us all safer.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), about 29 percent of the workforce was able to work from home. Ninety percent of higher-wage workers received paid sick leave compared to lower-income workers, according to BLS. Just 31 percent of workers with salaries in the bottom 10% were allowed paid sick leave.

Among the working poor, Black workers will witness an even greater impact.

A Golden Opportunity for a Green Stimulus

Read the full article from The New Republic, here.

Providing both Democratic and Republican talking points—about government waste and excess, for instance—Data for Progress found at least 60 percent of respondents supported the idea of green industrial policy to boost a number of concrete technologies: smart grids, electric buses, renewable energy, battery technology, and building retrofits with a focus on low-income housing. Investments toward underground high-voltage transmission lines and electric minivans and pickup trucks also polled well. The only technology for which poll respondents seemed to dislike the idea of federal backing was meat alternatives like Beyond Meat. Report authors Daniel Aldana Cohen, Thea Riofrancos, Billy Fleming, and Jason Ganz also found strong support for federal funding of graduate programs in fields linked to green technology, such as engineering.

“Americans seem fine with a mixed economy. If anything, they’re excited about it,” said brief co-author Aldana Cohen, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania. “The Republican Party and the mainstream media will tell you that Americans want markets to be the leaders. Respondents were excited for the government to support things that feel even minimally like a public good, even when they’re told the private sector would do a better job.” Riofrancos, a Providence College political scientist, argued that the results show an appetite for the state to be something more than a “handmaiden to capital.”

Rising home values: As investors cheer, low-income owners despair

Read the full article from Buffalo News, here.

Like hundreds of other low- and fixed-income homeowners in fast-appreciating neighborhoods, the Howells fear they can’t keep pace with the speed or the scale of the reassessment. The project, which concluded in September and will hit city tax bills next July, logged steady growth in most neighborhoods, though some parts of the city saw no real appreciation, and others experienced staggering spikes.

Average assessments spiked most dramatically on the West Side, a Buffalo News analysis of more than 60,000 preliminary assessment records shows. They increased by as much as 272% on the blocks south and west of Symphony Circle, raising property tax bills by hundreds and even thousands of dollars.

Residents of a number of traditionally working-class and mixed-income neighborhoods, including Allentown, the Fruit Belt and Elmwood-Bryant, also saw assessments jump far above the citywide norm, hiking tax bills, escrowed mortgages and rents. Citywide real estate values grew at four times the rate officials predicted in 2015, according to The News’ analysis.

Fighting gentrification and displacement: Emerging best practices

Read the full article from The Next System Project, here.

California’s Bay Area is home to one of the country’s worst housing crises, where despite soaring rents there are still far more empty homes than unhoused people. In late January 2020, a group of unhoused mothers—organizing under the name “Moms 4 Housing”—took matters into their own hands, occupying a home in West Oakland that had been vacant for two years. Despite their violent police eviction, the moms had overwhelming community support and media attention. Their occupation and organizing resulted in a historic win not only for the right to housing but also for a burgeoning strategy that communities are using to combat decades of racist housing policies, displacement, and gentrification.

The property’s absentee landowners, Wedgewood Properties, agreed to sell the home to the Oakland Community Land Trust, a nonprofit that buys land to maintain permanent affordable housing for low-income communities.

Though there is sometimes disagreement about how to define and measure displacement and gentrification (with some pompous claims that it’s not even a bad thing), the public and private strategies of disinvestment—which have long incubated the concentrated poverty experienced by communities of color—are undeniable: redlining, exploitative financial practices, white flight, tenant harassment, and predatory housing courts have resulted in the structural racism that undergirds our nation’s housing crisis.

Beneath Amherst’s Audubon Golf Course, a long-forgotten mass grave

Read the full post from Buffalo News, here.

It was a secret to all but a few people with long memories in the Town of Amherst.

In 1964, crews working to build a new roadway on the University at Buffalo’s Main Street campus dug up several graves. What was all but forgotten was where the remains were unceremoniously reburied.

In two locations on and near Amherst’s Audubon Golf Course.

Now, the town is figuring out what to do to give the dead a proper final resting place.

“This is what it is. We have what we have. Now, what do we do, and how do we do it in the right way?” Amherst Supervisor Brian J. Kulpa said.

As nation honors King, some local governments ignore the holiday

Read the full article from Buffalo News, here.

“It’s a battle over symbolic messages,” said Henry Louis Taylor Jr., a University at Buffalo professor who studies race and class issues and urban affairs. “The holiday is a symbol and a message that is connected to it. Resistance to that holiday is opposition to that message and everything that it is about.”

The effort to make King’s birthday a national holiday began days after the iconic African American civil rights leader was assassinated in 1968, according to an account from the History channel.

Will Buffalo Become a Climate Change Haven?

Read the full article from CityLab, here.

“Say Buffalo becomes this magnet that’s attracting everybody that’s looking for a good place to live. It will become the East Coast version of San Francisco,” said Henry Louis Taylor Jr., director of the Center for Urban Studies at the University at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning. “Will we essentially recreate what I call the ‘White City’? The White City is a city for white people and other groups who can manage to afford to live there.”

Keenan, the Harvard climate adaptation expert, said Buffalo could become another example of climate gentrification, a phenomenon already underway in Miami, for example, where property values are rising faster in high-elevation, low-income neighborhoods that are better protected against sea-level rise. Keenan said that climate gentrification exists on both the small and large scale.

Taylor said that parts of downtown Buffalo with new offices and apartments have already seen an exodus of black residents. He believes that, rather than focusing on luring developers to build loft apartments and boutique office buildings, what he referred to as “the San Francisco model,” the city needs to be willing to preserve affordable housing.

“The San Francisco, the Chicago model, the Washington, D.C., model, the New York City model — that’s the model that they’re using here. And they are caught between this idea that there is either this model that they’re using, or death,” Taylor said. “They’re frustrated because they can’t figure out how to get this square peg called ‘equity, equality, justice’ into this round hole called ‘the market.’”

Letter: Buffalo should have an MLK Boulevard

Read the full article from Buffalo News, here.

On Nov. 5, in a shameful move, voters in Kansas City chose to remove Martin Luther King Jr.’s name from one of its main thoroughfares. I found this disheartening. What were they thinking? Voters in Buffalo wouldn’t do something like this. Then, I realized that Buffalo is one of the only major cities in the country without a thoroughfare named Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. There are more than 900 streets named after MLK in the country, but there is no major street honoring MLK in Western New York.

Granted, in many places MLK Boulevard is found in the poorest section of a city. This is one instance where Buffalo’s late arrival to the party can be informed by mistakes made in other places and turned into an opportunity to do better.

Main Street in Buffalo is known as the dividing line between the predominantly white West Side of the city and the predominantly black East Side. It is time to change this image, erase this dividing line, and transform it into a symbol of unity. Buffalo can do better than places like Kansas City. Buffalo can send a message to the rest of the county that its central corridor is no longer a dividing line, but a place where the entire city comes together.

It is time for the Mayor’s Office and Common Council to come together and formally put a referendum on the 2020 ballot to change the name of Main Street to Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. Why not?

Exhibit highlights those working for better health

Read the full article from UBNow, here.

“The Future of Health in the City,” a new exhibition presented by the UB Art Galleries that highlights individuals working together to bring better health and healing to the Buffalo community, will open on Oct. 8 in the Connect Gallery at the Conventus building with a public reception from 5-7 p.m.

The UB Art Galleries is presenting the exhibition of portraits by artist Charmaine Wheatley in partnership with the University of Rochester Medical Center and in collaboration with the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus Innovation Center, the UB Center for Medical Humanities and Restoration Society Inc.

“These portraits are about hope; they show a dreamscape of social change,” said Henry Louis Taylor Jr. director of the Center for Urban Studies in UB’s School of Architecture and Planning and another of Wheatley’s subjects. “They are about the possibility of building a future city where well-being and wholeness reign.”

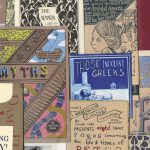

Arts beat: Innovative art, Mark Twain and a Musical Feast

Read the full article from the Buffalo News, here.

The Great Moments histories are the creation of Buffalo-based artist Caitlin Cass, whose work also has appeared in The New Yorker, The Lily and The Nib. For this exhibition, Cass has added original art and, with handwritten sidebars, says, “I will analyze my own canon in all of its messy, brazen eagerness.”

In a press release, Cass explains that she created the Great Moments comics in an effort “to make a history that prioritized failure instead of victory … the anticlimactic fizzling out instead of the path to progress.”

…

In describing the images, Henry Louis Taylor Jr. of UB’s Center for Urban Studies said, “These portrait are about hope; they show a dreamscape of social change. They are about the possibility of building a future city where well-being and wholeness reign.”

Apple Commits $2.5 Billion to Ease California Housing Crunch

Read the full article from The New York Times, here.

Apple on Monday announced a $2.5 billion plan to address the housing crisis in California, becoming the latest big tech company to devote money to a problem that local lawmakers and economists believe it helped create.

The iPhone maker’s plan includes a $1 billion investment fund for affordable housing and another $1 billion to buy mortgages. Apple also intends to make a 40-acre, $300 million property it owns in San Jose, Calif., available for new affordable housing.

Apple’s housing plan is a response to the increasing pressure Silicon Valley’s tech giants are under to play a more active role in the region’s housing crisis. As local tech companies big and small have boomed, they have flooded the region with hundreds of thousands of highly paid employees.

The Futures Garden

Read the full article from Buffalo Rising, here.

Just when you think that gardens couldn’t be any greater in Buffalo, comes along The Futures Garden. This Grassroots Garden is located directly across from the Marva J Daniel Futures Preparatory School #37 (Futures Phoenix), which is just down Carlton Street from The Medical Campus. On my way to visit a friend who lives a few doors away from the garden, I made a pitstop to inspect the sustainable grounds in all of their glory.

This garden has it all – giant rain barrels, composting, raised beds, beautiful signage, places to sit and ponder, solar power, hand painted garbage cans, flowers, veggies, and even a mini library. To me, this garden is about as inspirational as it gets.

Daring Imagination: Growth in Buffalo and Utica

Read the full article from The Houghton College Blog, here.

Houghton’s extension programs are intended to serve students who would not otherwise be able to access a Christian liberal arts education, and who would be highly unlikely to come to Houghton’s residential campus. The focus on tutoring, language development, mentoring, community support and accountability has resulted in impressively high completion rates (over 80% in both Symphony Circle and Houghton College Utica).

Pierre Michel, a member of the Class of 2011, recently assumed the leadership of the oldest of Houghton’s extension sites—Houghton College Buffalo: Symphony Circle. The son of Haitian immigrants, Pierre brings his own life experience to the Symphony Circle site, along with his previous work in leadership roles at two other educational institutions. Thus far, the program has primarily served refugees on the west side of Buffalo.

Erie County Corrections Advisory Board expected to be approved next week

Read the full article from WBFO, here.

The Erie County Legislature held a public hearing Thursday evening, but not a single speaker showed up. That was unexpected, because the hearing revolved around the plan for a Corrections Advisory Board, which has been controversial.

Earlier in the day, Erie County Sheriff Tim Howard told the Legislature’s Public Safety Committee he would go along with the creation. That was unexpected as well, as he has been unhappy about recreating a board that fell out of existence six years ago.

The sheriff told the committee he wanted “an open-minded, honorable advisory board,” not one “to advance a political agenda,” and that its work might benefit his department. That was such a breakthrough that hours later, no one showed for the evening hearing.

Prisoners Are People Too Announce Regional Conference

Read the full article from Challenger Community News, here.

Prisoners Are People Too is hosting a Regional Conference in collaboration with the Alliance of Families for Justice on Friday, May 3, from 5:30-8 p.m. and Saturday, May 4 from 8:30a.m.-3:30p.m. at Mt. Olive Baptist Church, 701 East Delavan Avenue . The conference, whose theme is “Changing Criminal Injustice,” will highlight the strategies that we can use to improve the lives of the incarcerated, the formerly incarcerated, and the victims.

Activist-scholar Dr. Henry Louis Taylor, Jr. will be the keynote speaker on Saturday, May 4. Dr. Taylor is the Founding Director of the Center for Urban Studies at the University at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning. His research, focusing on issues of race and class has made him an expert in assessing systemic factors, fueled by racism, that frequently lead to criminal convictions.

The cost of suspending driver’s licenses

Read the full article from Investigative Post, here.

The laws are making criminals out of tens of thousands of residents and straining court systems; yet in the case of debt-related suspensions, several experts said they provide little to no public safety benefit.

“We are taking people who are already on the economic edge, we are criminalizing them and increasing the burdens and hardships on their lives,” said Henry Louis Taylor Jr., a professor who studies race and class issues at the University at Buffalo.

Each year, a torrent of people with suspended license charges wind up in Buffalo City Court, clogging up judges’ dockets and bogging down public defenders.

Another Voice: Scammer isn’t the real source of blight on Buffalo’s East Side

Read the full article from Buffalo News, here.

A 2017 housing opportunity strategy study commissioned by the city found that most East Side housing units are moderately to severely distressed and located in underdeveloped neighborhoods with low market demand.

HouHou should be punished for his racketeering, but more important, Buffalo’s prime blighters should be exposed. The real predatory profiteers are the rental property owners who make hyper-profits by charging high rents for poorly maintained and distressed rental housing units, and the land speculators who purchase properties and hold onto them without making any improvements until more profitable opportunities can be found.

The City of Buffalo is also complicit in the East Side neighborhood blight. The city poorly maintains sidewalks, streets and vacant lots in those neighborhoods. And, their shamefully weak rental registration process makes possible the existence of a prosperous low-income rental market that exploits the poor and those on the economic margin.